Currently, no government entity or franchise industry organisation seems to know how many franchisors and franchise brands exist in Australia. The numbers thrown around vary greatly. If it was a requirement that all franchisors and their brands were to be registered on a public government register, this problem would not exist.

One of the key benefits to having a public franchise register is that it would enable franchisors, franchisees, lawyers, professors, journalists and regulators to have access to the same information. They would be able to compare and critique the available data, to make more informed decisions for themselves and others.

Journalists, professors and lawyers would have the resources to dive deep into the data and disclosure documents and publish easily digestible reports on the strengths and weaknesses of various franchise brands, which would help guide less sophisticated individuals into making a better choice when buying a franchise.

Regulators would be able to easily identify disclosure documents that don’t meet the standards set out in the Franchising Code of Conduct and potentially catch systemic practices early before too many people are impacted.

This must be a government run public database that can be accessed by anyone at no cost. If this service was to be run by industry, it would not be transparent, and all encompassing and accessing information would be costly. For example, it might cost $300 to view a copy of a franchise brand disclosure document – assuming it is able to be accessed at all. If a franchisee wanted to compare 10 brands, the cost would be prohibitive, especially given that they would most likely need to pay a professional to provide an analysis.

That would also mean that you would not see journalists, professors and lawyers comparing the top 100 franchise brands, again, because the cost would be prohibitive.

Having a public franchise register is key. Having journalists, professors and lawyers do the research that a franchisee would never be able to afford enables franchisees to make better decisions and decrease the chance of them becoming a victim. Franchisors that are not rated highly in public reports will naturally have to pick up their game or run the risk of not surviving.

A public franchise register would also be great for ethical franchisors that do a great job and treat franchisees well. This would be reflected in independent public reports. They would no longer have to compete on unfair ground against franchisors that cheat and cut corners to get ahead, because public analysis would highlight good and poor practice.

Register FundingA public franchise register could easily be funded by franchisors for a minimal cost that is not prohibitive. For example, if the registration fee was $300 + GST per year, per brand, revenue would exceed $300,000, given there are over 1000 brands. The small fee would be easily affordable for each franchise brand.

Technical StuffThe cost to produce the initial software and website would be quite reasonable if the concept we propose is introduced.

We would expect the cost to be between $50,000 and $300,000 to build a system that receives structured data submitted by a franchisor, which is then publicly displayed at no cost to the public.

A software tool that is built right would not require data entry from government employees. This would keep operational costs low. The government may wish to have an administrator who checks all submitted data for general errors prior to approving the entries for public display.

Registration fees would provide at least $300,000 per year to host the website, approve data entries and add extra tools over time, for example, to compare data between years. To securely host this service should cost less than $10,000 per year.

As for data moderation, if there was only a requirement for a franchisor to enter data once per year between 31 October and 30 December, labour costs would be minimal.

Systems can be designed in such a way that it is almost impossible to enter the wrong data, such as entering dates and amounts. This assists in enabling the user to input data with ease and without having to think too much.

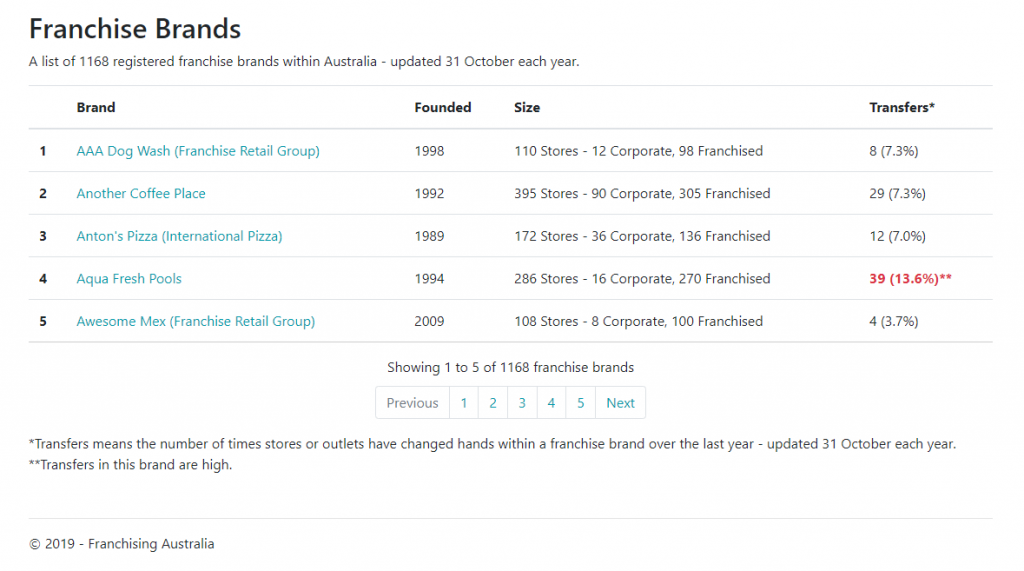

What The Register Could Look LikeGiven that we have extensive website, database design and construction knowledge in our office, we took the liberty of building a basic mockup website with sample data in it to demonstrate how it could look and the kind of information that could be easily gleaned by anyone viewing the public register.

You will note in the screenshot below you can see:

- The total number of franchise brands in Australia – as at 31 October 2018

- A list of all the brands that you can page through

- Where the brand is owned by a group, the software programmatically included the group name in brackets

- The year each brand was founded

- The total number of stores and the breakdown between corporate and franchised

- The total number of store transfers that occurred in that brand over the last year

- Where transfers are high, the software algorithm has indicated transfers are high – this could help to identify potential churning and system could automatically alert the relevant regulator who could make further inquiries. It also acts as a safeguard for potential investors or franchisees

Brand And Store Data

Brand And Store Data

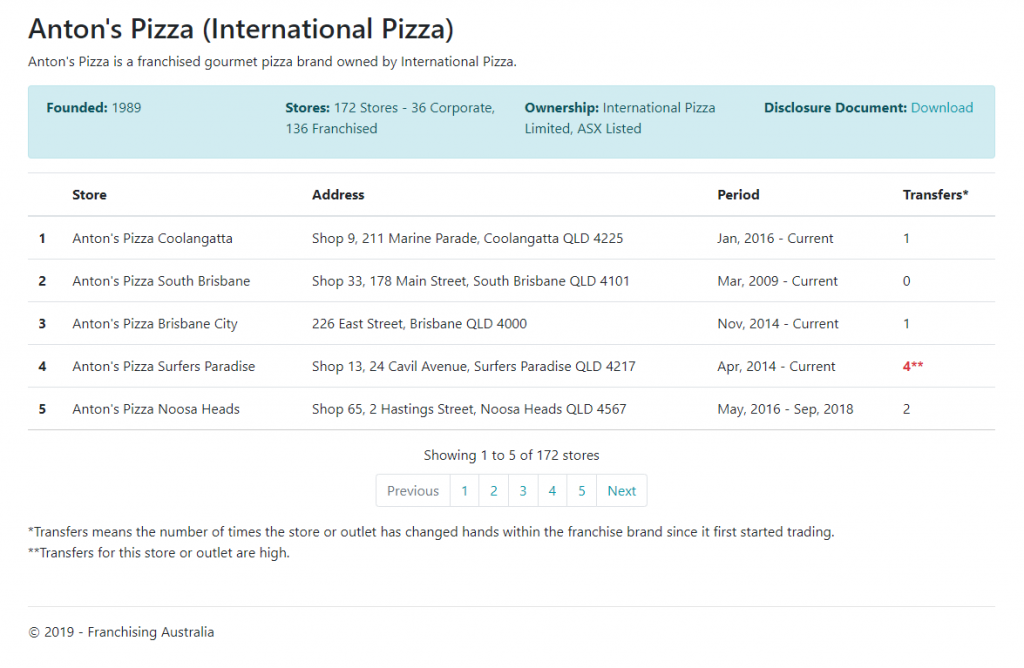

By clicking on a brand you could then access more information about the brand and important store data.

You will note in the screenshot below you can see:

- A small description of the brand that is entered by the franchisor – it could be something up to 300 words

- An information bar on the brand that contains ownership information – such as, if the company is listed on the stock exchange – and a link to the most recent disclosure document

- The name of each store, the address and the date it opened to current day. If it closed in the last year, the closure date is displayed

- The total number of transfers since the store opened. If a franchisee went into liquidation and corporate operated the store and sold it again, that would count as two transfers. Again, having this data publicly available would make it very hard for a franchisor to start churning a store without raising the suspicions of many and triggering regulator attention.

Code Requirement

Code Requirement

A simple requirement could be included in the Franchising Code of Conduct that states “A franchisor is required to register each franchise brand on the government register and pay the registration fee. The franchisor is required to comply with the terms and conditions of the website and ensure all information supplied is accurate. The register is required to be updated for every franchised brand and must be updated on or after 31 October each year and by no later than 30 December. Failure to comply with this clause may incur penalties and or enable imposed restrictions on the franchisor.”

Reduced Regulatory CostCurrently, if a regulator wanted to conduct an investigation into the fairness of disclosure documents being used in the top 10 food franchise brands, accessing the information would be costly and time consuming. Notices to produce would need to be served and some push back may be experienced.

Now imagine the same scenario with our suggested public register. It would literally take two minutes to gather the documents from the proposed brands. The regulator would also have the added benefit of being able to conduct an investigation without the franchisor being aware and mobilising lobbyists to attempt to disrupt the investigation.

With franchisees having access to a free public register, they could sit at home on a Sunday night and look at 20 potential brands of interest. In seconds they could download the disclosure documents and view the transfer rates for the brand, including the transfers of specific stores they are interested in. This would significantly reduce the regulatory burden, because franchisees would be less likely to buy from brands with high transfer rates and by observing the differences between various franchisor’s disclosure documents.

Published: 27 September 2019